"We need an intervention"

INTERVIEW: Henry Dimbleby spoke to Field7, explaining why he's quit the government as its Food Tsar.

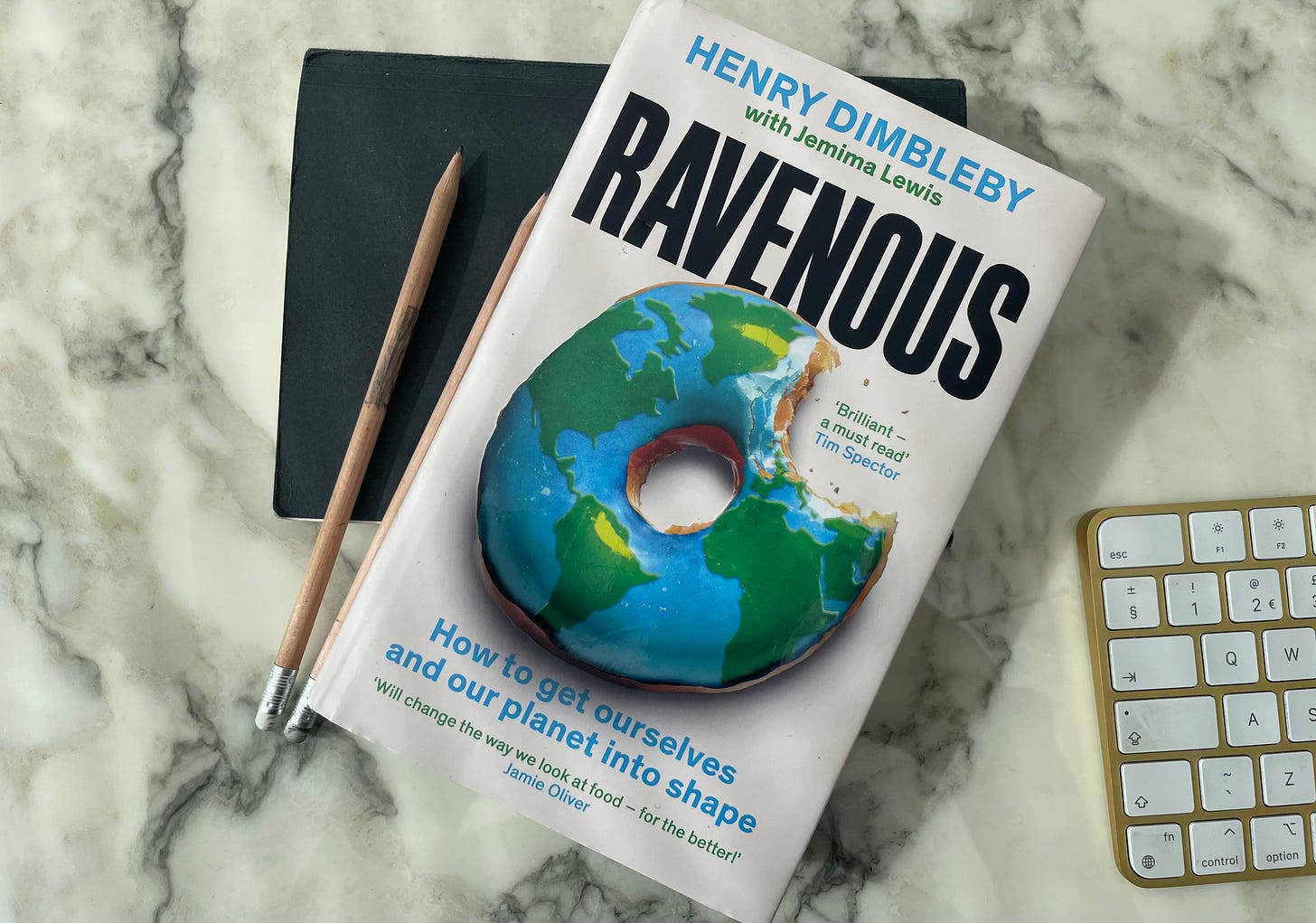

It’s hard not to raise an eyebrow and suspect a degree of orchestration behind the timing of Henry Dimbleby not-so-quiet quitting his role last weekend and the launch of his book, Ravenous.

If the publicity means more people read it, good on him.

Having produced an in-depth, two-part, state-of-the-nation National Food Strategy report for the government last year, Ravenous is a faster paced version made for normal people.

The former UK Food Tsar paints a picture of an out-of-control industry which has put the country on the brink of two impending mega crises: obesity and climate.

If you scroll down you’ll find a Q&A with Dimbleby and the policies around climate he is still pushing for.

Among the takeaways when we spoke were:

😵💫 Working for five secretaries of state and three prime ministers in three years.

🦠 Brexit, Covid and Ukraine.

📊 Unlocking data.

🥩 The impossible politics of meat.

😖 And why Liz Truss banned him.

Welcome to the Field7 newsletter

Utopia or dystopia?

Henry Dimbleby is partial to pickled onion Monster Munch. He makes this admission along with revealing the jibes he gets from his young daughter about his weight. He says so to illustrate that all of us are prey to the irresistible might of the easy, cheap and more-ish processed food juggernaut which dominates our lives.

Our food system is responsible for a third of the UK’s emissions. It costs us £6bn a year in avoidable disease and illness. Over 28% of the population is clinically obese.

“We created a food system to avoid mass starvation… we changed our diets to match the system. That diet is making us and our planet ill.”

Dimbleby was commissioned to produce a national food strategy in 2019. The brief was to find a sustainable (in every sense of the word) way for the country to feed itself for decades to come.

As cofounder of Leon, Street Feast and the Sustainable Restaurants Association he had been around the block enough times to have a rough schematic of how the business of food works.

He had some familiarity with government machinery when he advised on children’s school food in 2013.

This time, Michael Gove, as part of Boris Johnson’s government, gave him access to a small army of civil servants and data crunchers for this more wide-ranging task.

The report took him to farms, supermarkets, Big Food companies, households among other corners of the food ecosystem. He delved into the knotty political and financial tensions that lay behind what appeared sclerotic, stultifying and often self-harming decisions.

The ideas he proposes from his research are less theoretical, rather the perspective of someone who envisaged from the outset they would be applied in the real world and make a difference. He appears to emerge with a clearer sense of what’s possible and what’s necessary, believing a utopia or a dystopia could lie ahead.

He calculates it’s entirely possible for the UK to be self-sufficient if needed, to feed itself “in a u-boat situation”, let alone find a path to divert it from its current trajectory of hurtling to health and climate disasters.

And yet…

Political leadership (or lack of) are where things get choked. The book is filled with smart, informed, exciting and pragmatic policy ideas which have stalled or failed to take off despite his attempts over the last three years.

Dimbleby attributes the lack of progress from successive weak governments:

“Fear of unintentionally creating new problems, pressure from the food industry, public scepticism and a truculent media ready to punish any whiff of nanny statism.”

He adds:

“Government food strategy is not a strategy at all. It' is merely a handful of disparate policy ideas, many of them chosen because they are unlikely to raise much of a media storm.”

All of this leaves one wondering how he didn’t have a Falling Down moment in the employ of a historically chaotic government. (He explains how it went below).

Q&A. Government needs to act now

What led you to quitting your government role?

It was the stuff around obesity and health. They [the government] were actually moving towards restricting advertising on junk foods which would’ve been a good first step. But they’ve gone backwards.

Why was this such a critical issue for you?

It’s hard to exaggerate the implications. In ten years time, whoever is in govenment will have to deal with sick bodies thrown at it from obesity. It’s on everyone’s mind in the health service.

What about climate, food and the role of the government?

We treat Earth’s resources as costless and infinite. It’s actually worse. Our political systems actively encourage destruction of nature. Governments subsidise activities that destroy the environment. We need to think of our land as not just delivering food, but also restoring our biodiversity and carbon sequestration.

How do you see government’s role?

There needs to be an intervention to stop making the least healthy and most damaging food for the planet the most profitable. It’s possible with how governments incentivise things.

Your time as food tsar took place during a crazy period in UK politics. How did that affect your work?

Well there was an extraordinary amount of turnover. Between 2019 and 2022 I reported into five secretaries of state for environment, food and rural affairs (Defra): Michael Gove, Theresa Villiers, George Eustice, Ranil Jayawardena, Thérèse Coffey.

Wow. That’s mental.

Yes. And even so you accept that it’s inevitable that government departments act as clients for their sectors.

What does that mean?

You end up in a situation where Defra are worried about food companies, DCMS worried about the impact on children’s programming, Health worried about impact on the NHS. They’re all competing to protect their department’s interests.

You need a strong Number 10 to bring this together and resolve this conflict. Things work better when you have that central control.

And there certainly wasn’t a stable Number 10 during this period.

Yes, it was quite erratic. I worked under May, Johnson, Truss and Sunak.

Who was the hardest to work with?

Truss banned me from meetings because I disagreed with her on trade. She was so ideological, she didn’t seem to like hearing arguments from different points of view.

In the book, you write extensively about meat. The fact 20% of our land is used to produce 3% of our calories. Can’t we address this with policy?

Government will find it very difficult to intervene here. If you put a carbon tax at the current carbon traded price, meat would go up a lot, and it would be expensive. Mince would double in price. It would bring down the government.

That’s quite bleak.

In five years time, when we’ve had many more climate related events, that could change. It’s amazing that people used to smoke on aeroplanes and we didn’t angry. We need to move faster to address the issue of meat. Two thirds of agricultural emissions come from methane, but it’s not just methane; it’s freeing up the land to restore biodiversity and carbon sequestration.

It wasn’t just the state of the Tory party that was turbulent was it?

No, the food industry had four potential no-deal Brexit deals, one pandemic and a war in Europe to contend with in my three years in the role.

You’ve mentioned how Covid threw a spanner into the research.

Yes but in some ways the pandemic provided an illuminating stress test on the resilience and adaptability of the UK’s food system to a major shock.

What did the industry do?

During the pandemic, we had to suspend competition law, we had to see how food was moving and allow shops to look at supply chains.

Was there something you learned in that?

So many things could be fixed with making the right data available transparently; everything from the use of land, biodiversity and the supply chain. There is an enormous amount of waste in the system and we could address that with data.

Why is this so difficult to implement outside of an emergency like Covid?

The weird thing is the food companies are excited about sharing data. The nervousness is that transparent data would create political pressure around competition. But this is surmountable.

The former CTO from Ocado is an interesting figure who outlines how big an impact transparent data would have around waste. Another is Tim Berners Lee who has thought about questions around who gets access to what data and at what level.

But ultimately all of this can only come from sustained political leadership.

The If-I-Was-In-Charge wishlist

At the end of Ravenous, Dimbleby outlines a number of ‘actions for government’.

Here are the ones related to climate.

Use public money that was previously allocated to the Common Agricultural Policy to pay landowners to deliver public goods. (This is giving farmers money for carbon sequestration and biodiversity projects).

Create a ‘Rural Land Use Framework’ based on the Three Compartment Model. (85% of UK farmland is currently connected to livestock - providing only 32% of our calories. A plan to wean us off by measuring, analysing and fixing).

Define minimum standards for trade and a mechanism for protecting them. (In the trade deals post-Brexit, a list of criteria should be set out which include environment and carbon emissions).

Invest £1bn in innovation to create a better food system. (Carving this money into new agriculture projects, alternative proteins and a separate kitty to improve the food system. Instead of putting money solely into academia, direct some towards farms trying creative ideas and startups).

Create a National Food System Data programme. (Dragging the food system into the modern world where activity is tracked and analysed to see what’s working and what could be done faster, cheaper, easier. He propose two areas: 1) land and 2) the supply chain built around us buying our groceries.)

What do you think of what Henry Dimbleby is proposing? Reply to this email.